A Key to the Kingdom

by Keith Gordon

Lot 751 at the auction of the collection of the late Kelly Tarlton in Auckland attracted my attention. It was November 2002 and the auction of Kelly’s Shipwreck Museum collection, including a number of items of historical diving equipment, had attracted a large interest and the bids were high. A Siebe Gorman double dive pump had sold for NZ$13,000 despite the auction catalogue indicating a pre-sale estimate of $4000-$6000, and a 12 bolt SG helmet with a SG pump had sold for $34,000. I was beginning to give up hope of successfully bidding for any item of my old dive mate’s gear. However Lot 751, described as – “An Italian hand operated dive pump and aqua-lung,” stirred something in my memory from diving days long past, and had a pre-sale estimate of $300-$400; I thought I would have a go at bidding. I lost – it sold for $900.

Although the system was incomplete, I went away from the auction trying to recall where I had come across this piece of equipment in the past. It was not until some time later that the puzzle was answered. I was re-reading an old diving book that had held the interest of us young divers back in the mid-1950’s, “The Marvellous Kingdom” by Pierre Labat – and there in the book were photos of this same apparatus.Translated from the French, the book describing the diving adventures of a group of French youths had made a big impression on our young minds. There were not many books available on diving in those early days of sport diving and we eagerly absorbed anything we could get our hands on in our quest to learn more about the new world we had ventured into. Labat’s descriptions of diving played with our imaginations and were fodder for our aspirations to explore the ocean. Using homemade surface supplied gear Labat described his first dive:

Slowly I went in. At first the water was foamy against the glass, almost impenetrable; then the miracle happened. The sea closed around me; the light became liquid and without shadow. The world of man disappeared and my real life begun. At first I could see nothing but a deep blueness, a calm blue without blur or crack, only with here and there an arrow of deeper light like those that filter through the stained glass windows of a church or through the foliage of a forest interior, shafts of diffuse brightness, some slanting, some parallel, some even converging, like the spokes of a wheel, on some mysterious depth.

With descriptions like this we were sold; in those days we didn’t have, nor needed, underwater images on TV or in glossy dive magazines to hook us on diving. But Labat’ss book also describes dangers involved with diving and probably helped to instil some caution that helped us to survive. Likewise the book publishers sobering short note that followed the Preface by J.Y.Cousteau: ‘We deeply regret to record that in August, 1953, Pierre Labat dived for the last time into the Marvellous Kingdom.’

It is a great book and well worth the read.

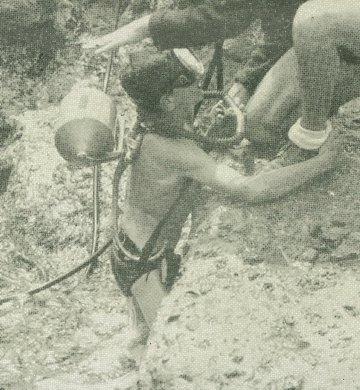

However back to the piece of dive equipment that had attracted my attention at the auction. Following inquiries I tracked down the person from whom Kelly had obtained the apparatus. He informed me he had got it off one of his fellow workers when they were constructing the Wellington Harbour slipway, probably in the late 1950’s. I also contacted Neil Walker who had won the auction bidding. Neil owns Stirlings Dive Shop in Auckland and had purchased the old Galeazzi dive system to display in his shop, along with other historical dive gear, to show his dive students of today how things were done in the past.The brass and copper construction of this surface supply diving system, is of a quality this well-known Italian maker of dive helmets is renowned for.

The double cylinder surface pump supplied air down to a copper reservoir tank strapped to the diverÆs back, then through a manifold to a twin hose mouthpiece assembly. The maker’s plate on the tank states; Ditta Roberto Galeazzi – La Speizia – Apparecchi Per Lavori Subacque A Qualsiasi Profonditaö (Company Roberto Galeazzi – La Spezia û Equipment For Underwater Works – At Any Depth). The apparatus enabled Labat and his young fellow divers to make the transition from vertical diving using primitive open helmets, to free-swimming in a horizontal position. They later went on to use Commeinehes GC 47 and Cousteau-Gagnan scuba systems, but it was the primitive surface supply systems that first opened the doors to the ‘Marvellous Kingdom’ for these young divers. Many older readers will no doubt recall experiences with using similar equipment in their endeavours to enter the submarine world those many years ago.